Is it possible to slow the rate of ageing, or do biological constraints limit its plasticity?

A new study published in Nature Communications, uses data from the Species360 ZIMS database to shed light onto the aging theory “the invariant rate of aging hypothesis”, which states that every species has a relatively fixed rate of aging.

The study was led by Prof. Fernando Colchero, member of the Species360 Conservation Science Alliance and statistics professor at the University of Southern Denmark, and Prof. Susan Alberts, Duke University and further included researchers from 42 institutions across 14 countries, including CSA members Prof. Dalia Conde and Dr. Johanna Staerk.

In the study, the researchers studied birth and death patterns of nine human populations and compared these with data from 30 non-human primate populations, including gorillas, chimpanzees and baboons living in the wild and in zoos.

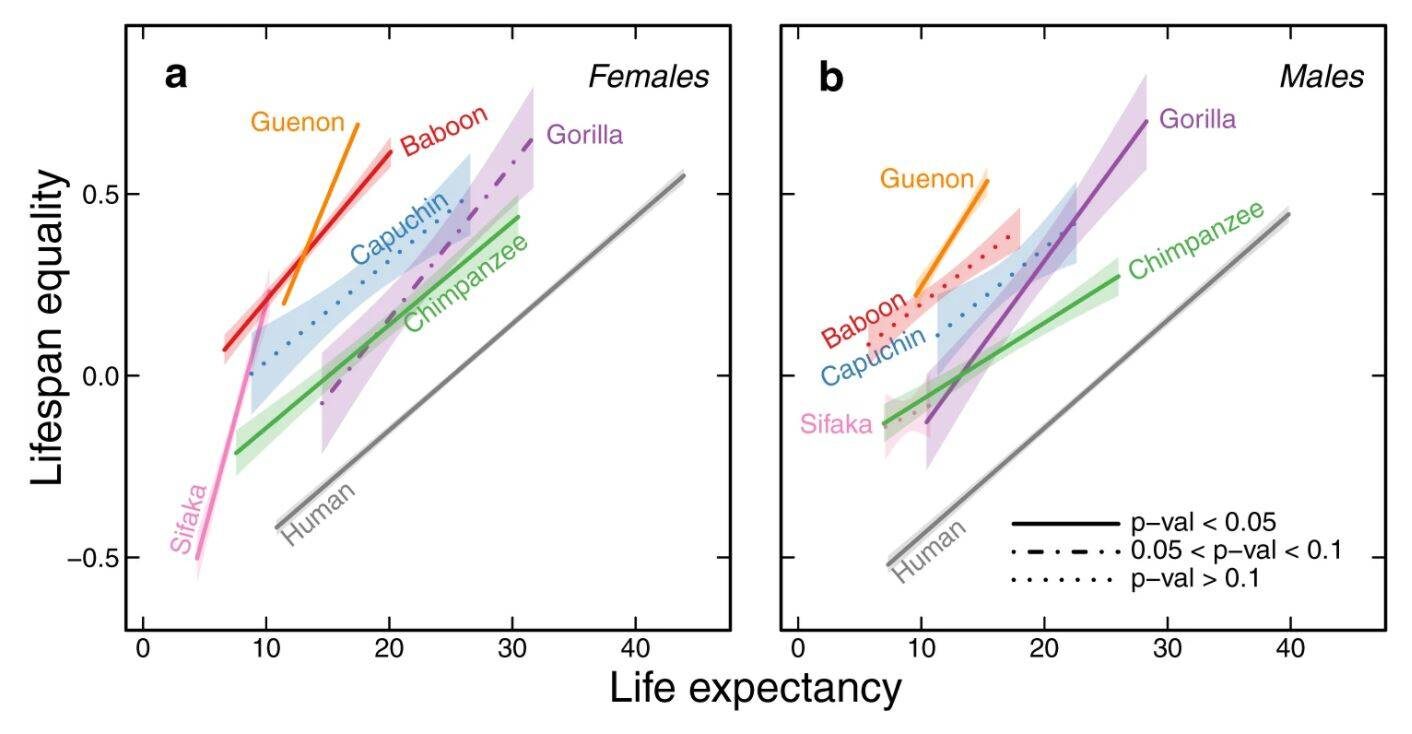

They analyzed the relationship between life expectancy, this is the average age at which individuals die in a population, and lifespan equality, which measures how concentrated deaths are around older ages.

Their results show that, as life expectancy increases, so does lifespan equality. But this is not because humans have slowed their rate of aging; the reason is that more and more infants, children and young people survive and this brings up the average life expectancy.

Similar patterns were observed in non-human primates suggesting that this pattern might be universal among primates. For example, zoo populations showed reduced infant mortality compared to most wild populations, increasing their overall life-expectancies and lifespan equality in a similar way as modern humans living in Japan or Sweden compared to hunter gatherers.

By studying these patterns, the researchers were able to provide new insights into the mechanism of ageing.

This article is adapted from the SDU News. Read the full article here.

Read more about this study on the news; the Guardian and lifespan.io: